(Photo by Nancy Stone for Nourishing Hope)

Kirby Reed was 25 years old when he took his first jazz dance class — an enthralling experience that altered his life’s direction.

“I was hooked from that day on,” said Reed, now 61. “I felt free. I got out of my own way. I got out of my own head.”

At the time, Reed had been miserable in his day job as a banker. A native South Sider, he grew up with artistic leanings that hadn’t yet manifested. After that first dance class, though, he spent all his free time pursuing other opportunities to learn the craft, eventually earning a scholarship with the Joel Hall Dancers, a renowned Chicago dance company.

From there it was a swift ascent: Reed went on to teach and perform throughout Chicagoland and at competitions across the country. He developed his own unique fusion of jazz, modern and hip-hop dance styles, and had a knack for sharing it with others.

Perhaps most notably, he became known as one of Chicago’s most beloved and sought after dance teachers.

“His niche was 100 percent being able to teach dance,” said Amy Giordano, executive director of GUS, the Gus Giordano Dance School in Andersonville. “He could teach to all levels and all ages. The students just adored him.”

Reed went on to teach at institutions such as Joel Hall, the Gus Giordano Dance School, Columbia College and Frances Parker High School. His classes were touted among the top dance classes in Chicago in Dance Spirit Magazine. In 2003, he was voted top hip-hop dance teacher in the city in Chicago magazine.

It’s no hyperbole to say that Reed taught the art form to thousands of students. His life was busy and fun and deeply fulfilling.

Then everything changed.

Struggling with grief and loss

On a late morning in August 2009, Reed was teaching his first class of the day at Joel Hall when a student asked him why he was slurring his words. He denied doing so.

“The next thing I knew, I was on the floor,” Reed said.

He had suffered a stroke.

As he was being wheeled into the emergency room at a nearby hospital, he had another stroke and a heart attack, Reed said. Then, once in his hospital room, he had another heart attack.

Two strokes. Two heart attacks. All within an hour or so.

Remarkably, Reed was still alive but he was also forever changed. He was paralyzed on the left side of his body. He couldn’t walk or talk.

“I felt disfigured,” Reed recalled. “I couldn’t look at myself for months.”

So began a long, arduous and often lonely road of physical therapy and rehabilitation. He refused to accept that he wouldn’t walk and talk again. He rejected the likelihood that he was done with dancing.

His circle of friends grew smaller.

“A lot of people wanted to be around Kirby when he was teaching and choreographing,” Giordano said. “But when he had the heart attacks and strokes, they didn’t value him still in the same way.”

In Reed’s own words: “You really see who’s in there for good and who’s along for the ride.”

It turned out Giordano, daughter of the late Gus Giordano, a pioneer of modern jazz dance, was one of the people who remained in Reed’s corner for good. Before his health crisis, Reed taught advanced jazz dance at the school named for her father; their friendship has only grown and deepened in the years that have followed.

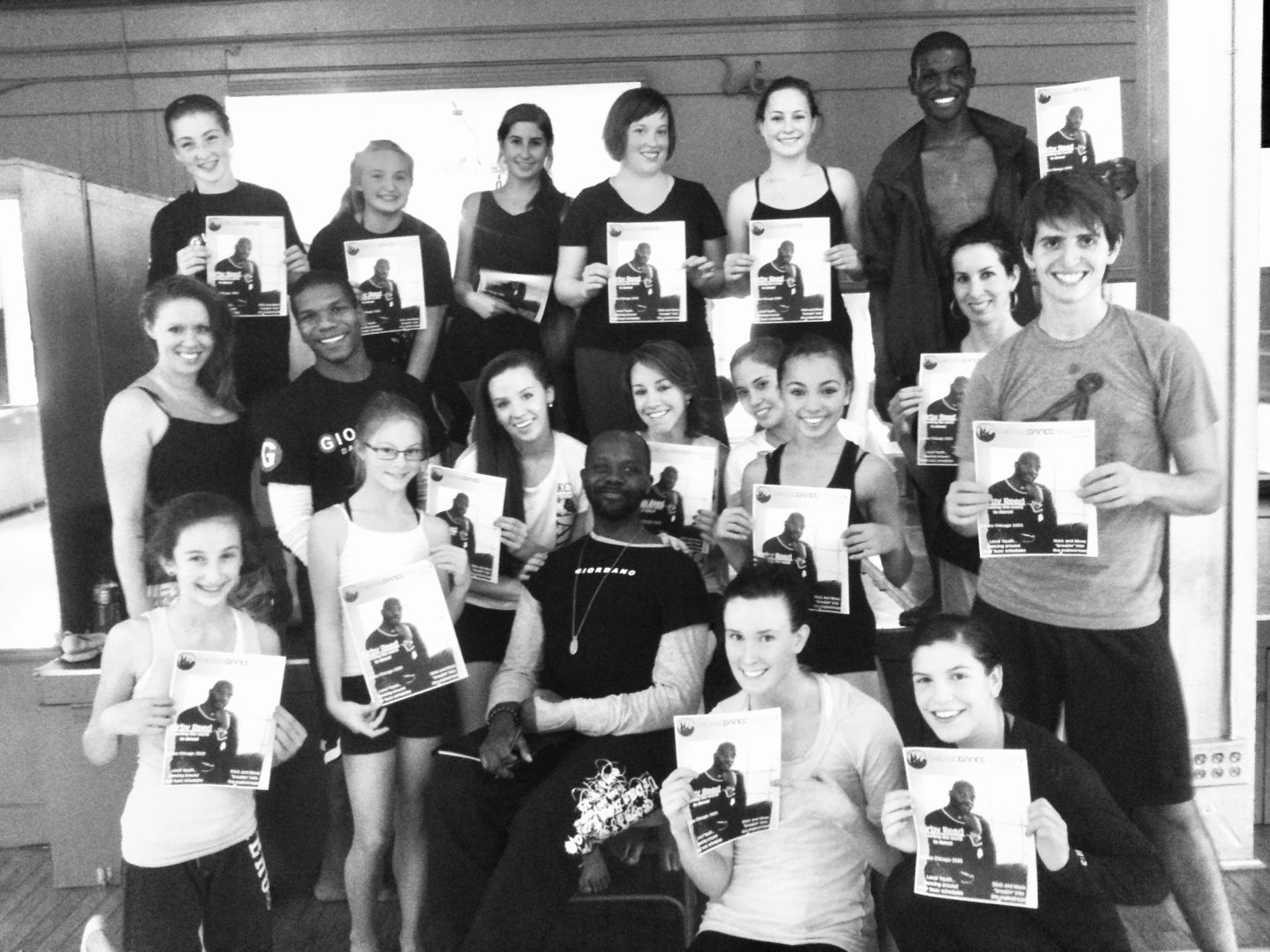

Kirby Reed (center toward the front) with a group of Giordano Dance students in 2010 — his first time back teaching at the school following his health crisis.

Drew Coleman, Reed’s personal assistant and best friend, was another stalwart source of strength and friendship. Coleman pushed Reed in his wheelchair to the lakefront for fresh air when he couldn’t walk. He helped him with errands, cleaning and personal grooming. They shared a deep and abiding love of music and dance.

This May, Reed said, Coleman died of a brain aneurysm.

“I’ve been struggling with grief,” he said. “I really miss him.”

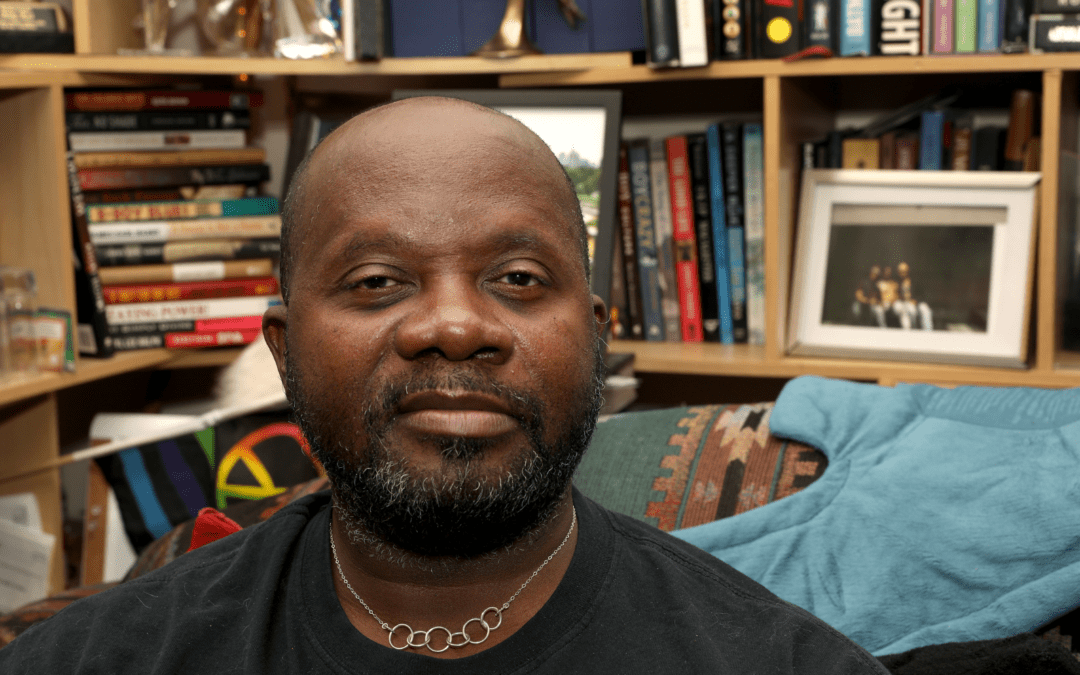

In a recent interview in his Bronzeville apartment, Reed opened up about his hardships. His living room walls were decorated with photos of loved ones, many of them now gone, and photos of his younger self — a lithe figure poised for graceful movement.

Kirby Reed in his Bronzeville apartment, surrounded by photos and memories. (Photo by Nancy Stone for Nourishing Hope)

The devastating loss of his friend has compounded personal challenges for Reed, which include the need for food assistance. Reed is one of almost 200 people on the city’s South and West Sides who are served by Nourishing Hope’s growing home delivery program. The program serves older adults and people with disabilities.

Once a month, he receives boxes of fresh produce, meat, dairy and other groceries through the program. Reed didn’t used to be someone who needed such help, but he’s grateful for it now.

“Food is always an issue,” Reed said. “You have to decide between food, medical costs or paying a bill. This really helps.”

‘Dance is for everyone’

Earlier this summer at the dance school, Reed sat in front of 65 college-level dance students and nodded his head to the beat. The students stomped and clapped, swayed and swaggered — a raucous and joyful rehearsal of dance choreographed by the master teacher. In unison, they dropped to the floor for a few beats and rose together as Reed pointed his right index finger to the sky.

(Video courtesy of Amy Giordano)

Today, Reed walks with a cane, though he sometimes uses an electric scooter if he’s going longer distances. He only uses his right arm and hand. He tires quickly.

Though his body has changed, some things have remained constant.

“I don’t think I’m a hardass but I’m real particular about my work,” Reed said. “I hold them to high standards. I don’t do lazy dancers.”

Here’s the truly remarkable and distinctly beautiful part of Reed’s story: He’s still teaching dance.

He teaches master classes at the school, where he’s become part of the community over the years. Regardless of their age, he calls his students “my kids” or “my babies.”

Everyone knows Kirby, Giordano said.

“They just love him,” she said. “They can see how much he truly cares about them..”

Giordano gives Reed work whenever she can, she said. It’s not charity — it’s family.

“I feel real supported and I know if anything happens, she’s got me,” Reed said of Giordano. “Amy makes sure I’m OK.”

Reed (standing in the center) poses with students in July at the Giordano Dance School, where he still teaches. (Photo courtesy of Amy Giordano)

Reed is still an exceptional dance teacher who creates a special bond with his students, Giordano said. The students give Reed life; they are the antidote to the pain and loneliness that he often feels. And in turn, he helps them to believe in themselves. What makes Reed a special teacher is his ability to give corrections while staying positive, Giordano said. That’s true for students of all ages and body types.

“Dance is for everyone,” Reed said. “Not everyone comes to be a professional dancer. It’s therapy for some.”

It’s a kind of therapy for Reed, too. He’s endured so much loss in his life. Many of his close friends died in the AIDS epidemic of the 1980s, he said. His grief for his friend Drew is often overwhelming. He doesn’t leave his apartment as much without him. He doesn’t feel safe.

On any given day, Reed experiences the loving community within the dance school and a profound feeling of isolation outside of it.

Despite it all, he’s still dancing, still reaching upward.

“I’ve had several lifetimes,” Reed said. “I just take it one day at a time. Life ends up putting you where you need to be.”