(A photo of Pamela Moore-Thompson’s family, from left: Big Ma, Dad, Grandma and Mom.)

When Pamela Moore-Thompson thinks about Black History Month, she starts with her hometown of Robbins, a proud Black community in Chicago’s south suburbs.

She reflects on her grandmother, known affectionately as Big Ma, despite her diminutive stature just barely clearing 5 feet tall. And she contemplates how Big Ma’s generous spirit was passed on to her father, Horace Moore, and eventually to her.

Do the right thing, and everything else will work itself out.

That was her father’s familiar refrain, a life philosophy that he lived through helping others.

In many ways, Moore-Thompson’s service on Nourishing Hope’s board of directors is a continuation of her own family’s remarkable legacy of helping others in need. Her family, and particularly her grandmother and father, believed in sharing what they could to alleviate the suffering of others. In Big Ma’s kitchen, that often meant a big pot of stew to feed the neighbors.

And in the same spirit, her father propped a ladder up next to their apple tree to help the neighborhood children access the fruit. They shared what they had, she recalled, even when they didn’t have much themselves.

“I truly believe what you put into the universe is what you’re going to get back,” said Moore-Thompson, 57, who works as vice president of talent strategy for UScellular.

Moore-Thompson’s story — and much of her outlook on life — is deeply rooted in Robbins.

When Robbins incorporated in 1917, it was considered the first Black-controlled municipality in the north. And though it’s among the lowest-income communities in Cook County today — a decline hastened in part by the vanishing of manufacturing jobs — Robbins has always been rich in Black history.

During the 1930s, Robbins was home to the first Black-owned airport, a place where Black men and women learned to fly — including pilots who later joined the famed Tuskegee Airmen who fought in World War II. (Learn more in this recent WBEZ story on the history of Black aviation in Robbins.)

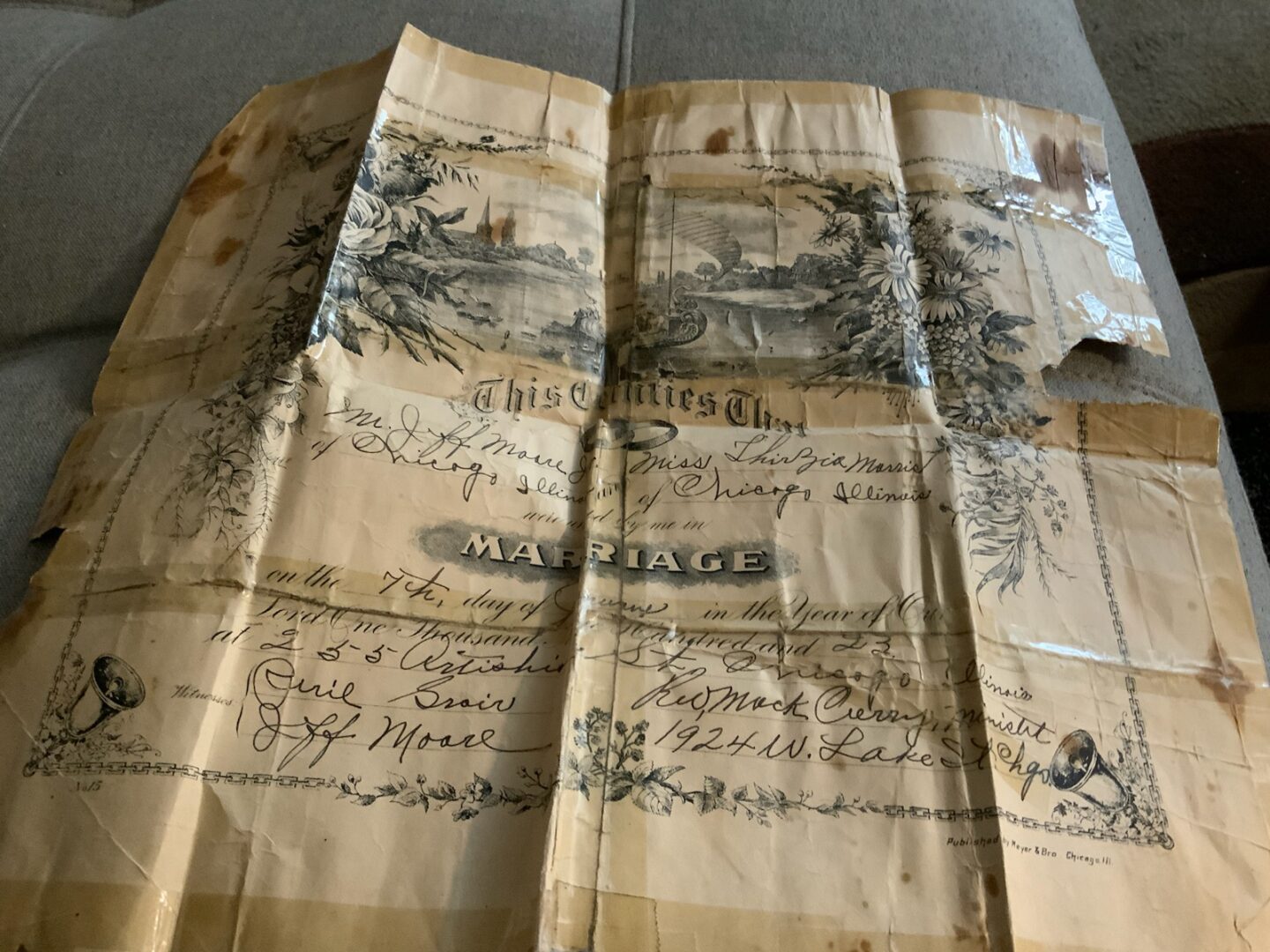

Big Ma, whose real name was Thirzia Moore, was born in 1895 and moved up from Chattanooga, Tennessee to Robbins in the 1920s and bought land for her family.

When she was a child growing up in the 1970s, Moore-Thompson recalled, Robbins was a tight-knit community where neighbors looked after one another. Children ran free in the neighborhood without fear of safety.

And, importantly, everyone she looked up to in the community was Black.

“We had Black doctors, we had Black dentists,” Moore-Thompson said. “We had these great summer celebrations that just celebrated African-Americans.”

“And so, that’s how I always knew that Black people could do anything.”

Big Ma was known as a generous and kindhearted person, a good listener and a source of comfort to people going through hard times. Friends of all ages would stop by to sit on her front porch and air their troubles.

Big Ma’s house in Robbins. She gave the adjacent lot to her son Horace, who built his own house for his family.

In her later years, Big Ma would set out walking on an errand because she didn’t drive, Moore-Thompson recalled, but friends and neighbors would see her and give her a ride.

“So I would see her all over the neighborhood in different people’s cars,” she said, laughing. “They’d be like, yeah, we saw Big Ma walking and we picked her up and brought her back home.”

Big Ma died at age 99, but her spirit of generosity was passed along to her family. Horace Moore, Moore-Thompson’s father, served in World War II and later worked for American Airlines for about 40 years, retiring as a crew chief. Her mother, meanwhile, cared for her and her four older siblings.

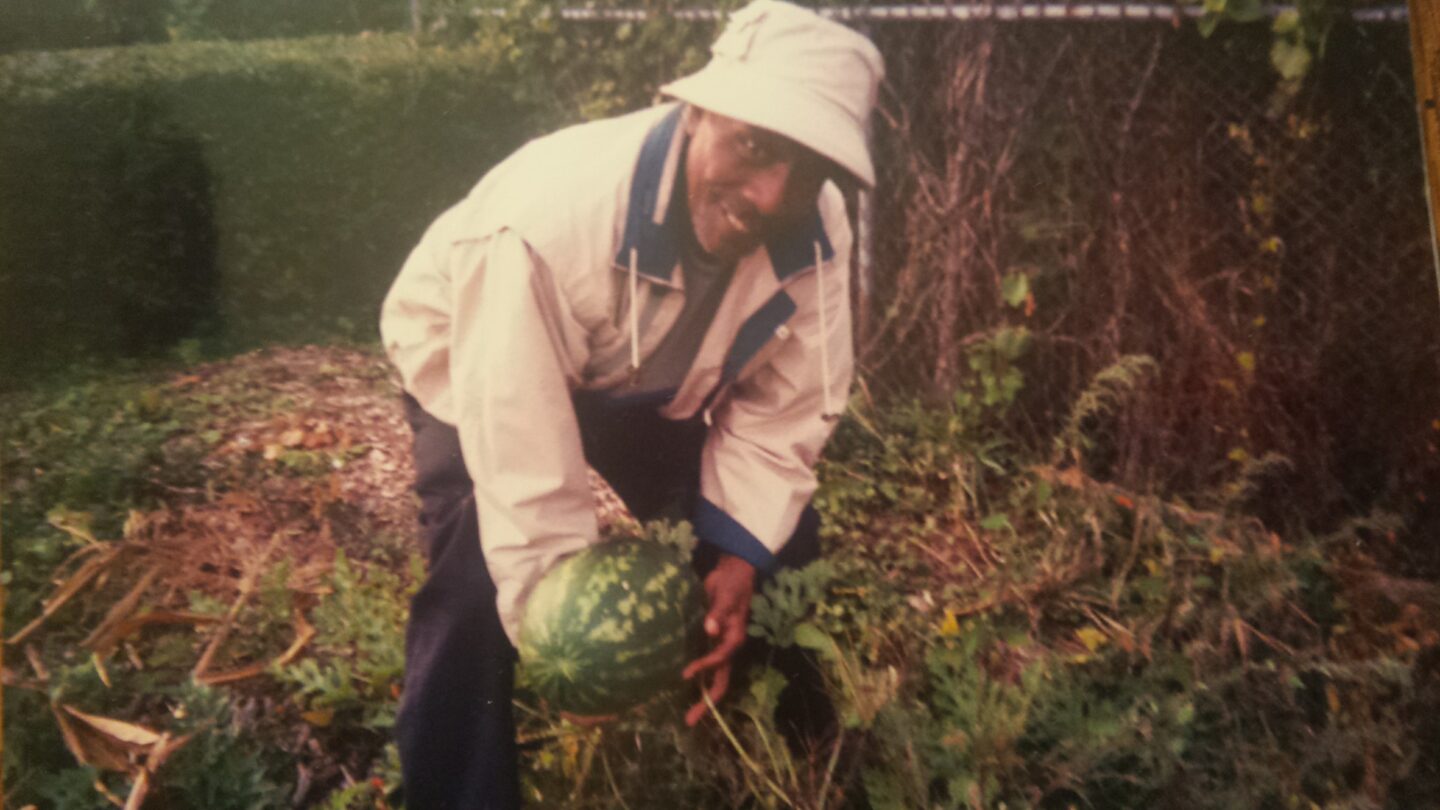

Often, Horace Moore would discreetly slide a silver dollar to his kids’ friends and cousins. He had an immense vegetable garden and regularly shared his vegetables with friends and neighbors.

“His automatic default was — what can we do to help?” Moore-Thompson said. “He tried to help people get jobs. He tried to help people get rides and food if they needed food. We never really questioned why.”

That kind of generosity is infectious. In her professional life in recent years, Moore-Thompson worked in the Loop, and regularly gave money and food to people experiencing homelessness, despite the occasional skepticism of others.

“Those people are not invisible,” Moore-Thompson said. “Sometimes people treat them like they’re invisible. They’re not invisible.”

“It hasn’t hurt me yet to give to people,” she added.

Do the right thing, and everything else will work itself out.